By Matt Roberts

Revised for 2018-19

Introduction

Welcome to the University of California, Irvine! As a student enrolled in the Humanities Core program, you will study a variety of cultural artifacts related to the theme of “Empire and Its Ruins.” Research will be important to your engagement with course material and topics, and the UCI Libraries is here to help you.

The UCI Libraries is home to several research librarians, who can provide you with expert service. To learn more, please visit the UCI Libraries’ Directory of Research Librarians.

To take advantage of the UCI Libraries’ resources for Humanities Core, please visit the Humanities Core Research Guide. You find the guide by visiting the UCI Libraries’ home page. Then click on the “Research Guides” Quick Link.

What is Humanities Research?

It is worth asking what it means to do research in the Humanities. As David Pan (Professor of German, UCI School of Humanities) writes, “[i]nterpretation is the primary method of the humanities because the meaning that humanities scholars search for is not a constant one. Rather, standards of meaning change when one moves in time and space from one cultural context to another. Negotiating this movement is the primary task in humanities inquiry” (6).

As Pan emphasizes, humanities work is an interpretive process. For instance, for your first major writing assignment, you must perform a close reading of a passage from the Aeneid. You will describe how the selection’s formal elements—such as symbolism or diction—support an overarching theme in the epic as a whole. While this assignment does not require that you conduct research related to the Aeneid, it nevertheless invites you to research the meaning of “symbolism” or “diction.” Let us therefore assess our information need and design a process to find the definition of, for example, diction.

Question: Where do we find the definition of a word or specialized term such as “diction”?

Answer: We find definitions in a dictionary.

Note that as the Aeneid is an epic poem, it is important to determine what “diction” means within a literary context. Therefore, let’s consult a dictionary of literary terms.

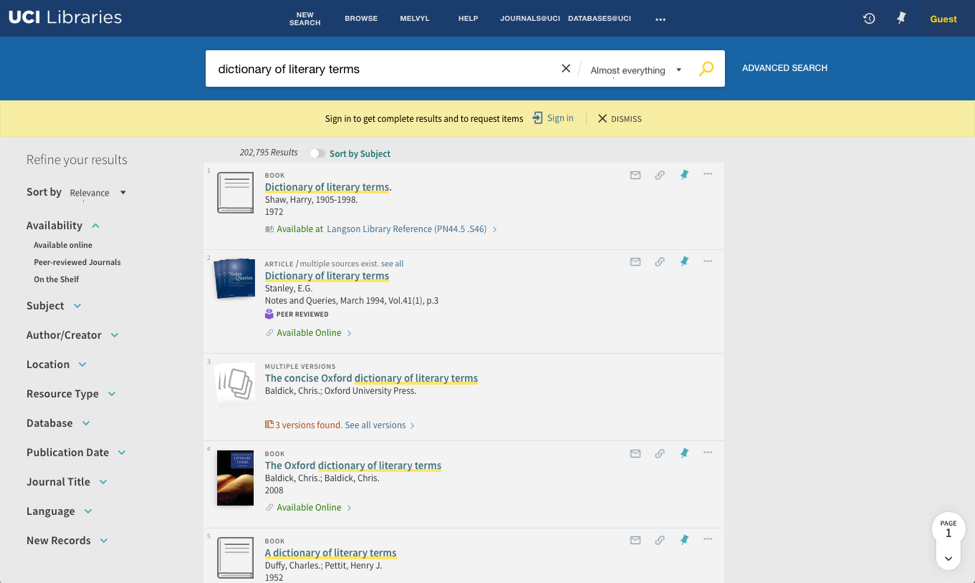

Question: How do we find a dictionary of literary terms?

Answer: Consult the UCI Libraries’ webpage. Then search Library Search, the new finding aid for the UCI Libraries’ catalog. Since we don’t know the exact title of the dictionary that we might use, we can simply search for “dictionary of literary terms.”

We must choose the title that best matches our information need. I chose The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms because Oxford University Press publishes exemplary reference materials. The green “Available Online” link takes me directly to this resource. I can then use the resource to search for the definition of “Diction.”

So, what have we learned?

- Research begins with a question (“What is diction?”).

- The research question(s) that we ask helps us to discover information.

- The kind of information that we need to discover will often determine what UCI Libraries’ resource to consult (e.g., a book, reference resource, database, etc.).

- Discovering information helps us to interpret an object of study.

- The interpretation of the object of study enables us to craft clearly argued responses to writing assignments.

In other words, humanities research is a strategic exploration whereby information discovery facilitates your interpretive abilities.

Doing Research: Primary Sources and Secondary Sources

As we have already noticed, the research process involves the ability to discover a source that provides information of some kind. It is therefore important to distinguish between sources so that you can readily access that information.

Scholars typically distinguish between kinds of sources, particularly between primary and secondary sources. As you will be reading a variety of texts this year, it is important to recognize that texts are not objectively primary or secondary. Ultimately, the extent to which sources are primary depends upon the questions you ask about them and the way that you use them (Arndt 93). For instance, a primary source is an object that bears witness to a historical event. Primary sources therefore call us to consider how they make meaning of the event to which they bear witness. On the other hand, secondary sources interpret a primary source. For example, if you were to write a paper that interprets how diction in the Aeneid characterizes human experience, you would be creating a secondary source.

Determining the difference between a primary source and a secondary source can be difficult. Let us explore each type of source in greater detail so that we can begin to understand what types of question we can ask of primary sources, and how we can engage with them in order to research secondary source material.

Primary Sources

On your syllabus, you will find a variety of texts, or sources, that you will read over the course of the year. In the fall quarter, these texts include, but are not limited to:

- Virgil’s Aeneid (19 B.C.E.)

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men” (1754/1755)

- J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

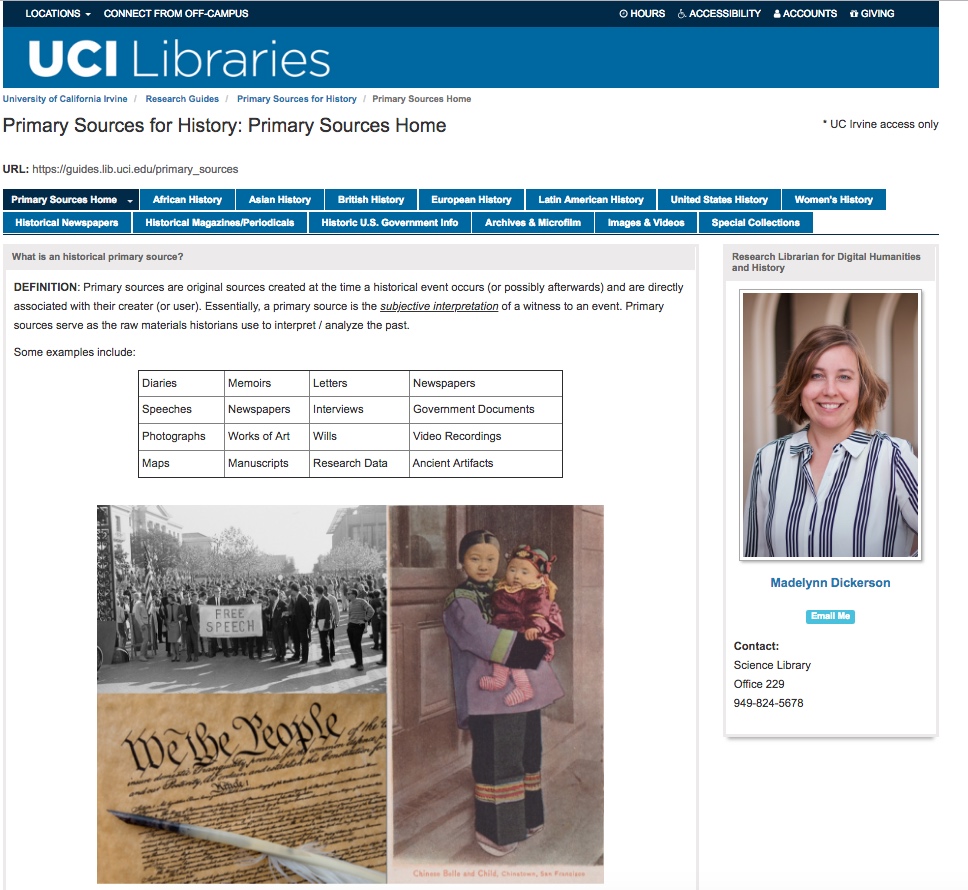

These are generally considered to be primary sources, but how can you be sure? To answer this question, consult the Primary Sources Research Guide, curated by the UCI Libraries’ History Librarian, Madelynn Dickerson.

According to this Research Guide, primary sources can include diaries, memoirs, letters, newspapers, speeches, interviews, government documents, photographs, works of art, video recordings, maps, manuscripts, data, and physical artifacts.

Question: Is the Aeneid a primary source?

Answer: Yes. Most often it qualifies because it is a work of art, specifically an epic poem. However, one might use the Fagles’ version of The Aeneid as a secondary source, demonstrating how the translation is an interpretation of the original Latin text and using that analysis to offer one’s own interpretation of the epic poem. You can learn more about the interpretive politics of translation from Giovanna Fogli and Nuccia Malinverni’s chapter on “Translation” in your Writer’s Handbook.

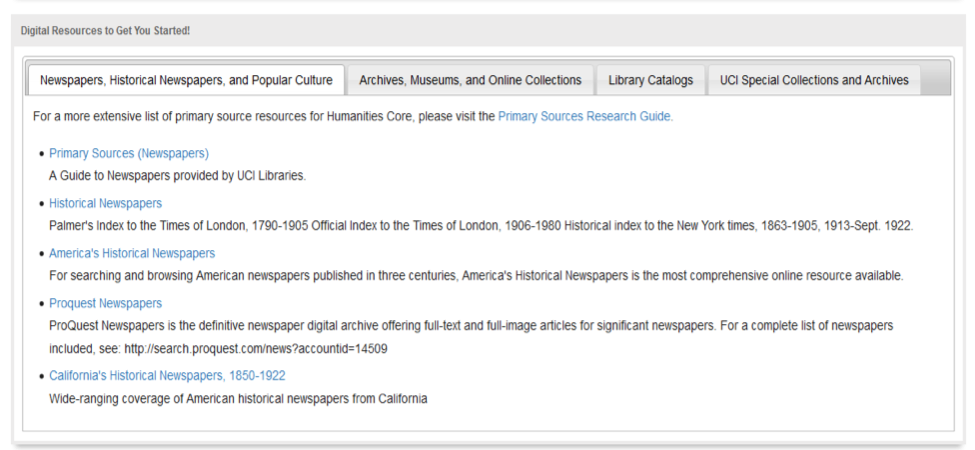

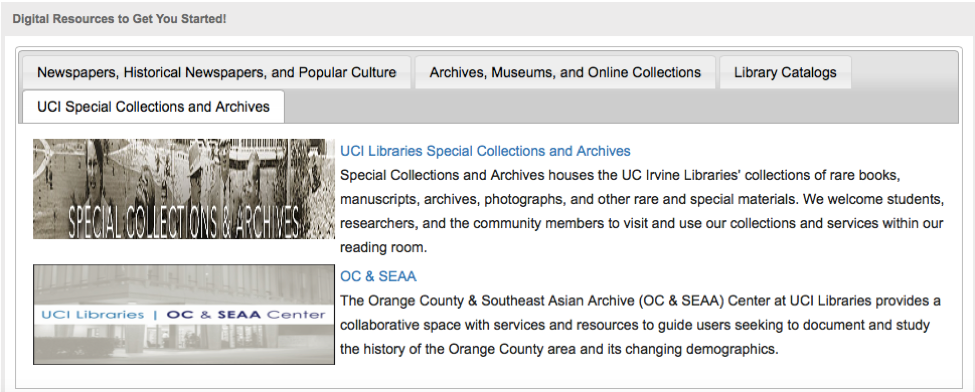

Throughout the year, you will be encouraged to find primary sources related to the topic of Empire and Its Ruins. To do this, it is useful to visit the Humanities Core Research Guide. Select the “Primary Sources and Artifacts” tab to locate primary source discovery resources.

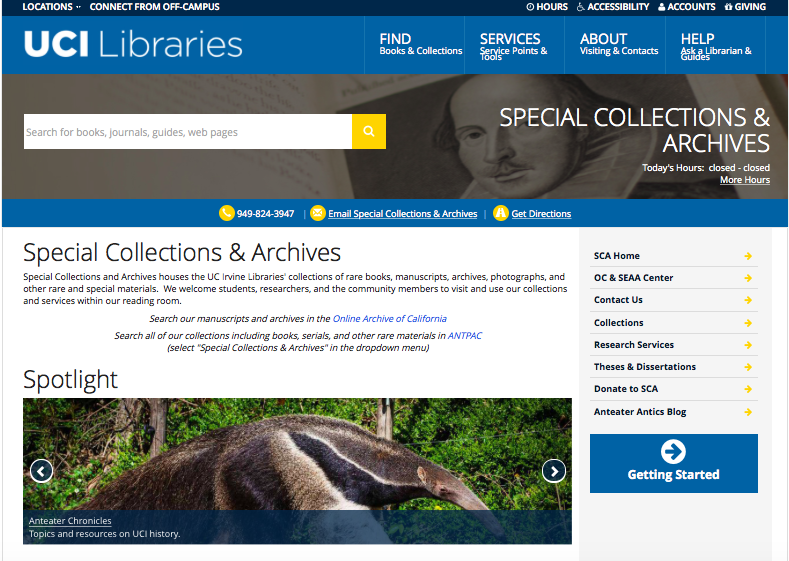

Additionally, you will have the unique opportunity to visit the Special Collections and Archives.

Follow the link to the SCA webpage, and you can discover a variety of primary source collections. Be sure to also visit the UCI Libraries’ Southeast Asian Archive webpage for a wealth of primary sources related to Empire and Its Ruins.

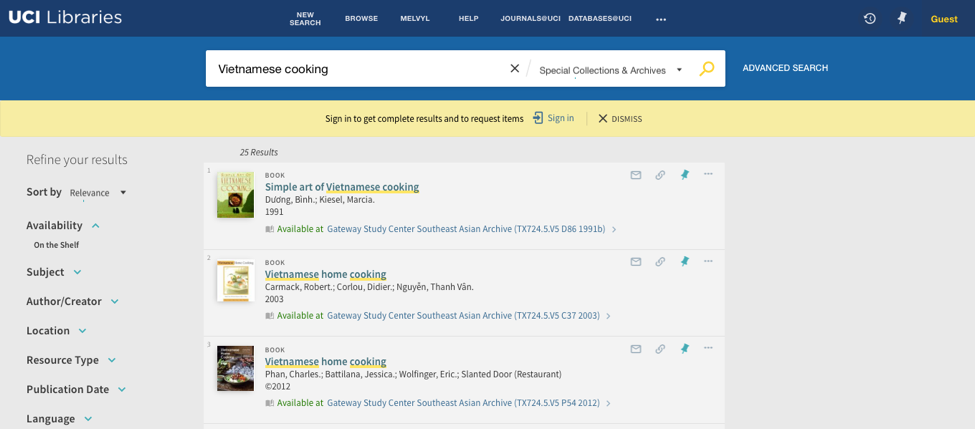

You can also use Library Finder to find primary sources and cultural artifacts in the SCA collection.

When analyzing a primary source, it is important to ask certain questions. Questions such as those listed below will help you to discover information, which you can use to interpret a primary source. In other words, questions such as these will help you to determine how a primary source makes meaning of the event to which they bear witness.

- Who made the primary source? What was that person’s race, gender, class? How, if at all, would that matter within the historical period in which the source is created? (Authorship)

- Where, when, and why was the primary source written/made? Does it describe specific attitudes of a historical period and place? What motivated its production? (Historical Context)

- For whom was the primary source written/made? For public or private use? Was it reproduced for a mass audience? How might that audience have used or responded to this source? (Audience)

- Of what is the primary source made? How might that shape how the source is understood and interpreted? (Materiality)

- What are the limitations of this type of source? What can’t it tell us? For whom is it not made available?

Simple questions such as these can help you to formulate more sophisticated research questions or topics of inquiry. You may therefore want to examine other primary sources or search for how expert scholars interpret the primary source that interests you.

Secondary Sources

When you do research, you are embarking on a journey that requires you to engage with how others interpret the primary source or sources that interest you. Whereas primary sources are original works that document an event as it took place, a secondary source interprets a primary source, often long after it was created. Secondary sources include, but are not limited to: Peer-reviewed academic books; chapters published in peer-reviewed academic books; peer-reviewed journal articles; newspaper and magazine articles published after, and therefore not explicitly covering, a historical event. Peer-reviewed works are considered to be most reliable in academic settings because they have been scrutinized and vetted by scholars to determine if the research presented makes a significant contribution.

Question: How do we find peer-reviewed journal articles?

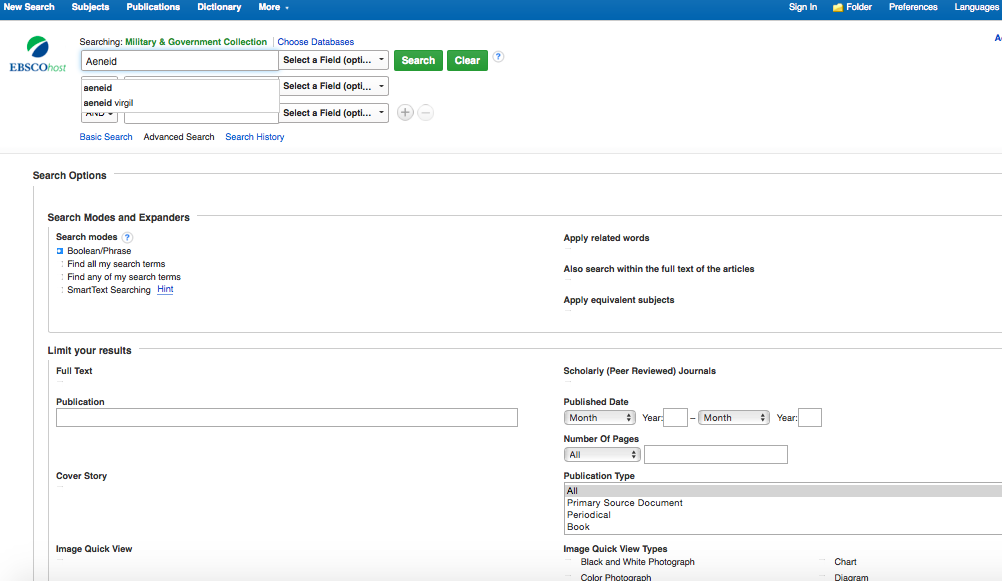

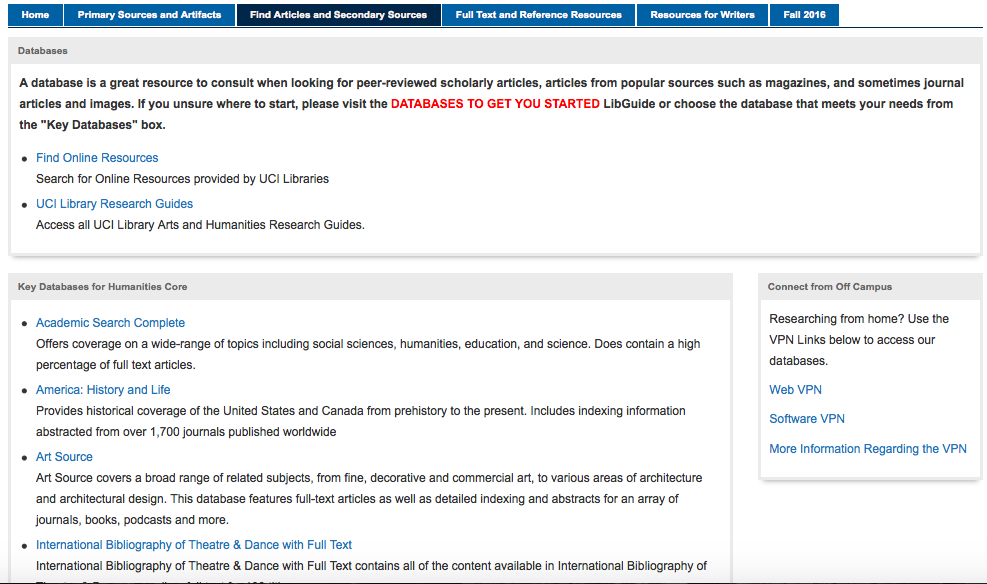

Answer: Let’s return to the Humanities Core Research Guide, where we will find links to, and descriptions of, the databases related to Humanities Core. Select the “Find Articles and Secondary Sources” tab to find peer-review journal articles.

I began my search with Academic Search Complete, which covers a wide-range of topics including social sciences, humanities, education, and science. It is therefore a good place to begin to do secondary source research. However, you can consult other databases such as the MLA International Bibliography, Project Muse, or JSTOR.

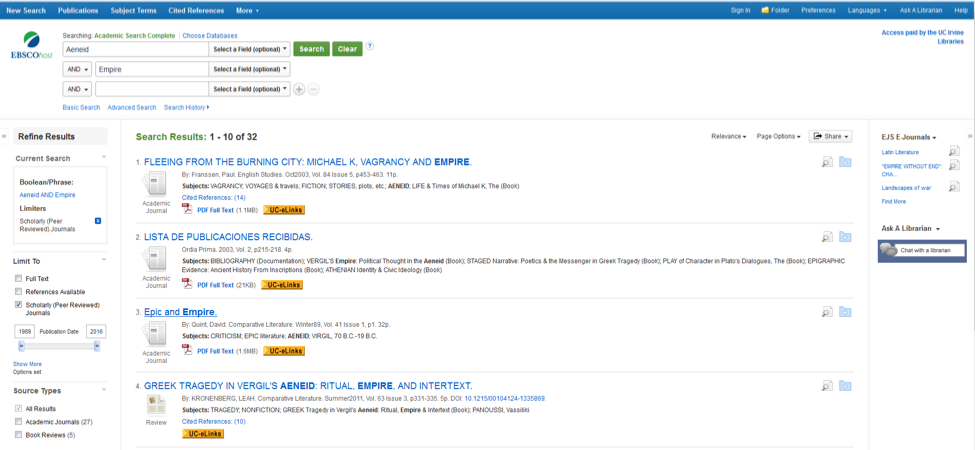

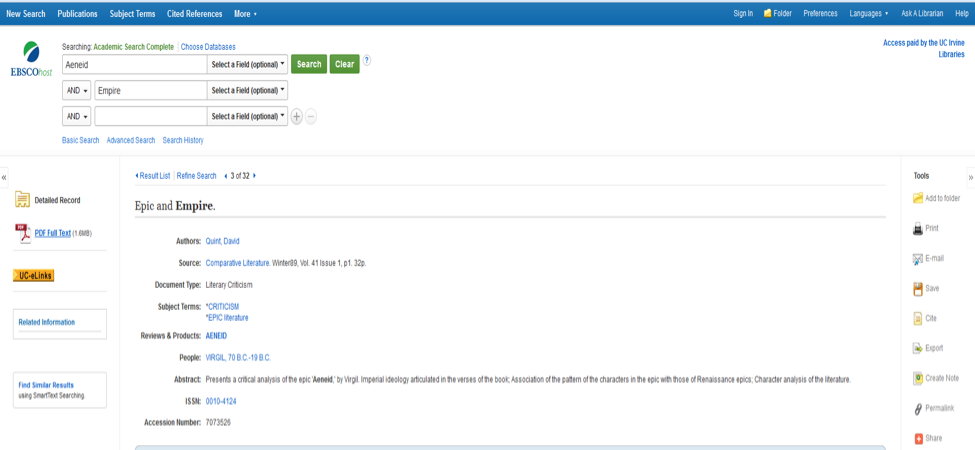

The above screen shot indicates how one might find scholarly articles related to the topic of the Aeneid and Empire. I also checked the “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” box to limit my results. This search populates the following result list:

The article entitled “Epic and Empire” appears directly related to our search. Selecting that article will open up the record for the article.

For this article, we can click on the “PDF Full Text” icon and download the article. For articles that do not have a link to the PDF, please click on the “UC E-Links” icon to search for alternative methods of access.

Please remember that secondary sources are interpretations. Consequently, as a researcher, situate yourself in an active role. In this way, you will understand that secondary sources should not speak for you or instead of you. Rather, you should integrate them into your analysis of a primary source to demonstrate your own contribution to a scholarly conversation on a topic that interests you. We do not do research simply to communicate how others have interpreted a primary source. We do research to discover how to interpret something for ourselves.

So, what have we learned?

- Primary sources are original sources created at the time a historical event occurs and are directly associated with their creator. A primary source is the subjective interpretation of a witness to an event.

- Secondary sources are scholarly or popular sources that interpret a primary source and can be created long after the primary source was created.

- Research is a process that requires us to question and interrogate the information that we discover in order to interpret an object of study. It requires the evaluation and integration of both primary and secondary sources.

- The UCI Libraries have several research resources that can help you to discover and choose primary sources and secondary sources that interest you.

- Research Librarians at the UCI Libraries are here to help you!

Conclusion

Please note that you will be able to take advantage of several of the UCI Libraries’ instruction and reference services throughout the year. You can meet with research librarians who specialize in specific disciplines to learn more about conducting searches and vetting sources.

Works Cited

Arndt, Ava. “What to do with Primary Sources.” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War, edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 90-94.

Baldick, Chris. “Diction.” The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. 3rd ed., 2008. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199208272.001.0001. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Imamoto, Rebecca. Primary Sources for History: Primary Sources. University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Pan, David. “What are the Humanities?” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War, edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 5-9.

Quint, David. “Epic and Empire.” Comparative Literature, vol. 26, no. 1, 2001, pp. 620-26.1. Academic Search Complete. Web. 16 Sept. 2016. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7073526&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 16 September 2016.

Roberts, Matthew. Humanities Core Course. University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.